At a time when technology makes it easier than ever to trick and mislead, media literacy is vital.

Yet too many Australians lack the necessary skillset to sort truth from false.

Ninety-seven per cent of Australian adults have insufficient ability to verify information online, a joint report by the University of Canberra, Western Sydney University, Queensland University of Technology (QUT) and RMIT University found in 2024.

The report also found a strong desire among Australians for more media literacy education to combat misinformation.

Michael Dezuanni, one of the report’s co-authors and QUT School of Communication professor, tells PIJI media literacy in Australia is still in its “infancy” – especially for adults.

“We know from research that only about one-fifth of students say that they get media literacy education in schools … really though, the main policy focus has been on schools,” he says.

“What [Australia has] really lacked is any kind of focus on media literacy for the community in general, or for adults.”

Under the proposed News Media Assistance Program, the Australian government has committed to developing the country’s first National Media Literacy Strategy over the next three years.

Details are currently scant, but Dezuanni – also the chair of the Australian Media Literacy Alliance (AMLA) – expects AMLA will be among those helping the government develop the upcoming strategy.

“AMLA has really been advocating to the federal government over the past five or six years, calling for a national strategy,” he says.

“As we understand it, AMLA will work closely with the federal government on the strategy.

“We’re not sure yet what shape or form that will take, but we’ll be starting, hopefully, a series of meetings with the [Communication Department] soon to start to work on what that strategy might be.”

Piecemeal efforts

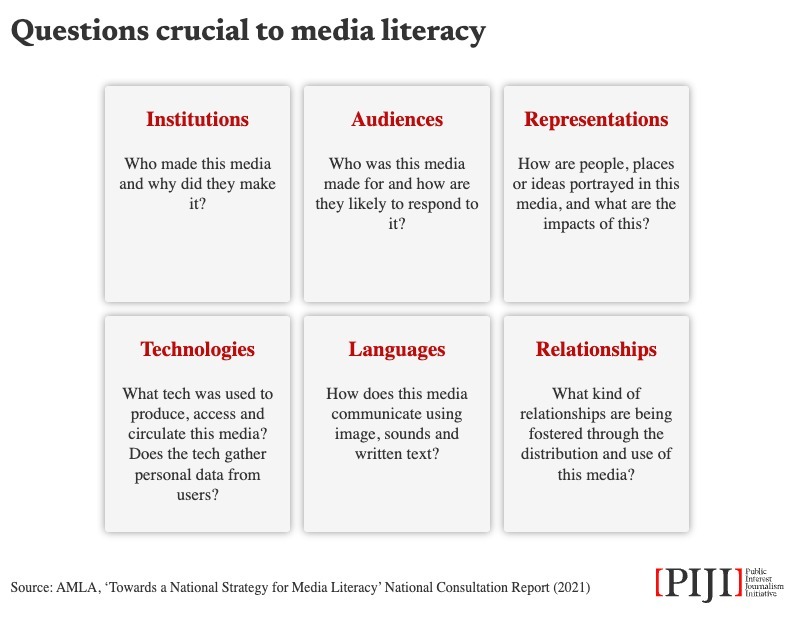

As noted in a 2021 AMLA report, in the absence of an official strategy, multiple organisations have taken it upon themselves to support media literacy education in Australia.

Journalist-turned-educator Bryce Corbett is among those at the forefront of these efforts as the founder of Squiz Kids, a kid-friendly daily news podcast, and Newshounds, a free media literacy resource created to be taught in schools.

In the vein of the iconic ‘Slip, Slop, Slap’ sun-protection campaign, Newshounds three-word slogan is ‘Stop, Think, Check’. Developed alongside primary school teachers, the gamified podcast has proved popular with teachers voluntarily seeking to implement media literacy education in the classrooms.

To date, Newshounds has been used in about 4500 classrooms around Australia and hundreds of classrooms in New Zealand. Organisations in the US, UK and Finland have also expressed interest in adapting the program, Corbett tells PIJI.

But he says the future of Newshounds is in jeopardy, as funding from Google is set to run out by March 2026.

Newshounds has petitioned the Australian government for assistance; the amount of funding sought has not been disclosed, but Corbett says it is an “absolute drop in the ocean in terms of government budget”.

“We’ve never wanted turn it into a commercial offering, because we really firmly believe that you don’t want … media literacy, or digital literacy, to be something that only … private schools can afford, because it should be a skill that is being taught to all kids equally right across the country,” he says.

The government has already invested elsewhere in media literacy education, but take-up has been left to the discretion of individual schools.

In 2022, the Australian government committed $6 million over three years to the Alannah & Madeline Foundation to make its digital literacy and media literacy programs available for free to Australian schools. Since then, more than 50,000 students accessed the digital literacy program, and more than 5000 students participated in the media literacy program.

The Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) has set elements of media literacy education across subjects like English and Media Arts in the national curriculum. The implementation of the curriculum is the responsibility of states and territories.

ACARA also launched a new resource this year to help teachers locate and organise media literacy themes across subjects, following a recommendation from the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters to prioritise media and digital literacy education in the Australian curriculum.

During recent overseas travels as part of a Churchill Fellowship for his work in media literacy education, Corbett realised Australia is “lagging behind” countries like Finland and Estonia, which have worked hard to build media-literate populations “by virtue of the fact that they share a border with Russia”.

“Australia has a way to go in understanding that this … should be a national priority, and I think we’ve gotten beyond the point where media literacy is a nice thing to have.

“The government needs to recognise this as a vital 21st century life skill, and … take the responsibility of ensuring that the population [including kids and adults are] taught how to think critically about information they’re encountering online.”

What dangers do misinformation and disinformation pose?

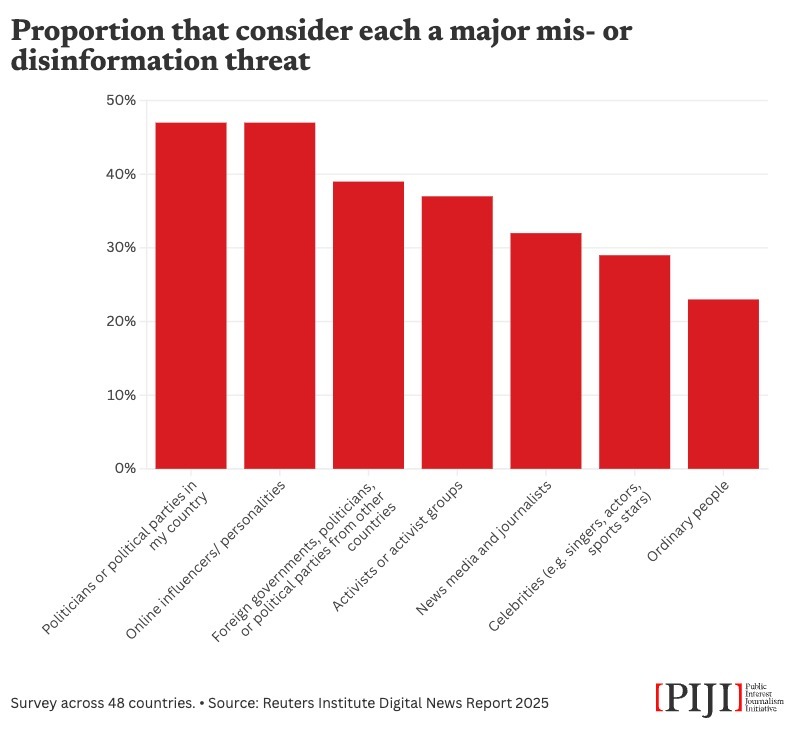

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2025 highlights misinformation and disinformation as the biggest risk to provoke global geoeconomic tensions over the next two years, above threats such as state-based armed conflict or cyber espionage.

The danger of mis- and disinformation includes, but is not limited to, the potential use for foreign or partisan parties to affect voter intentions, sow doubt about events in conflict zones, and cause mistrust of mainstream media.

Recent examples of these campaigns include:

- Ahead of the 2024 US election, X (formerly Twitter) users made thousands in revenue by posting election misinformation, AI-generated images and unfounded conspiracy theories.

- The 2025 Australian election saw mis- and disinformation campaigns targeting several political parties on platforms like RedNote and via AI chatbots.

- A fake BBC news report spread on social media reported Ukraine’s first lady was being kept under armed guard after trying to flee the country.

- Vaccination rates for diseases such as measles and polio fell in several countries, due in part to the growth of vaccine misinformation.

The recent suspension of more than US$268 million (A$412 million) in funding for the US Agency for International Development’s global support of independent media is expected to create a further surge of misinformation.

“There’s nothing less important than our democracy at stake,” Corbett says in explanation for the need to increase media literacy.

“Because we continue to see how mis- and disinformation can warp the outcome of elections around the world, can completely change the way people think, and increasingly can make them disengage with real, credible, quality news, and also disengage with the civic institutions that are really important to a function in democracy.”

Written by Sezen Bakan